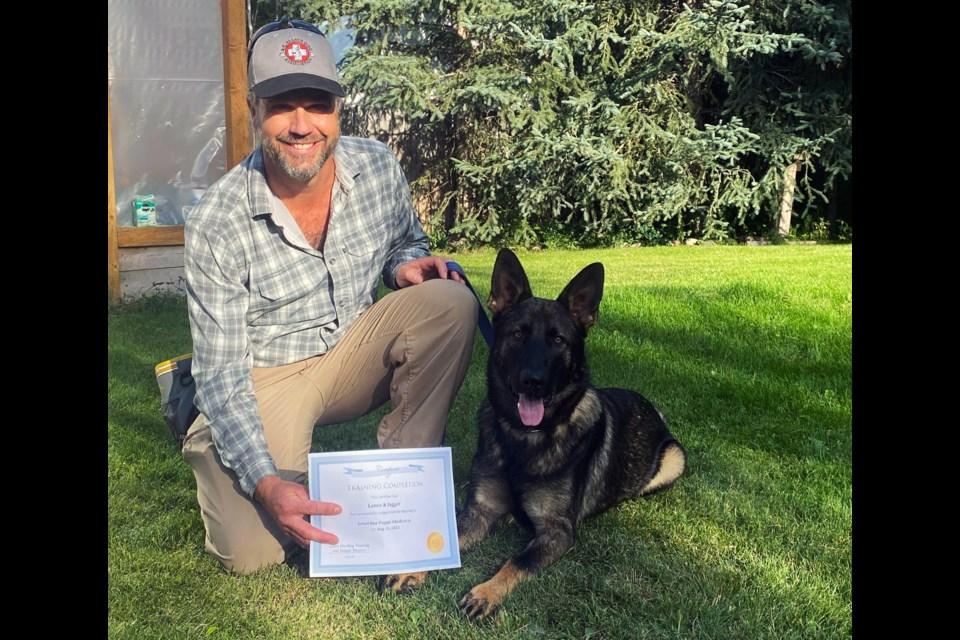

Two years ago, when Lance Barrowman wanted to train his dog Jagger to aid searchers in emergency rescues and offered his services to Houston Search and Rescue president Andy Muma, a 15-year SAR volunteer, Muma wasn’t sure what to tell him.

He wanted to say yes, but was unable to provide a guarantee that the dog would be put to use if needed.

It takes years of training to teach a dog how to aid in searches and Muma is well aware the RCMP canine teams in Prince George and Terrace are the only other potential source of a provincially-approved search dog team north of Kamloops.

Jagger and Barrowman passed the BC Search Dog Association training course at the top of the class and Barrowman is eager to progress to the next training stage but is unable to do so without approval from the province’s Emergency Management and Climate Readiness (EMCR) agency.

The problem is, three years ago, in a verbal declaration, the search and rescue director of EMCR imposed a moratorium on all of the province’s 78 SAR teams and their 3,400 volunteer members, which prohibits any of those groups from adding to their list of capabilities until the province has conducted a needs assessment study.

In search and rescue terms, a capability is any skill set or type of training that allows SAR members to respond to specific types of emergency situations or incidents. That includes tracking, swift-water operations, flat-ice rescue, winter responses, avalanche rescue and canine-assisted searches.

Muma says the moratorium has taken away all ability to add new capabilities despite repeated applications and requests from highly-motivated communities and SAR groups.

“We stand to lose both the dog and the handler if we can’t get approval from EMCR to move forward with this dog’s training,” said Muma. “Without approval we are prevented from both further training and the purchase of equipment due to liability issues.”

In the northwest region, the moratorium was cited by EMCR as the only reason to reject an application for tracking capability from Fort St. James SAR, despite the group’s established expertise as members of the BC Tracking Association. An application by Bulkley Valley SAR for flat-ice rescue ability was also denied by the province.

Muma submitted an application for a search dog canine capability for Houston SAR two weeks ago and has yet to receive a response from EMCR. He says there are other dog handlers working with SAR teams in Terrace and Dawson Creek that are seeking the same approval.

He wants to know why the province has suddenly decided it should control how local SAR groups operate and what services they are allowed to provide and he’s worried his crew of volunteers will leave the organization rather than have to deal with a government bureaucracy that restricts the services they provide.

“We’ve been operating in the Houston area for over 20 years and we work very closely with the RCMP, our main tasking agency and we know what we need, so we don’t understand why there has to be such micromanagement,” said Muma.

“The other problem I have is despite repeated requests from EMCR to give us documentation on the moratorium to let us know how long it’s going to be on for and to let us know what the needs assessment is all about and when it will be completed, in the three years I’ve been asking the director of the (provincial) SAR unit for this documentation I’ve never gotten it. I want to know why this hasn’t been made public.”

Muma has learned the province intends to lift the moratorium in another three years, which means SAR groups across the province will have waited six years to add to their list of capabilities to expand the scope of the emergency services they provide. That, says Muma, is leaving communities unprotected and is unnecessarily putting lives at risk.

“These capabilities immediately save lives and prevent the pain and anguish of a fatality due to the lack of approval to respond to a specific type of incident," said Muma.

Muma and Houston SAR manager Frank McDonald vented their frustrations in an email message sent Monday to Premier David Eby and Deputy Premier Lori Wanamaker.

“The moratorium decision and other examples (such as the ability to introduce new technology) have caused significant harm, eroding trust and impeding the operational efficiency of SAR teams,” Muma wrote. “The operational consequences include the squandering of volunteer time, damage to community trust, hindrance in fundraising efforts, discouragement and resignation of volunteers, and, most importantly, limitations in the ability to conduct effective rescues.”

In the wake of expanded powers coming to the provincial authorities since the Emergency and Disaster Management Act passed into law on Nov. 8, they want the B.C. government to audit the practices of the EMCR SAR unit and its decision-making process in hopes it will become less dictatorial to the search and rescue community.

“We are uncertain about how these expanded powers will be utilized and if there are mechanisms in place to monitor potential misuse of authority,” said Muma.

“Our sincere hope is that we can collaboratively work towards altering the provincial EMCR SAR unit's approach to one that is more enabling and supportive, fostering a true partnership with volunteers rather than a top-down regulatory stance.”