Standalone abortion clinics on Vancouver Island may start in Victoria and end in Nanaimo, but there are options farther north, say advocates — they just require contact with one of B.C.’s most highly sought resources: a family doctor.

A recent leak of U.S. Supreme Court documents detailing plans to overturn Roe v. Wade prompted B.C. Green Party Leader Sonia Furstenau to ask the premier during question period in the B.C. legislature May 19 about improving abortion access across the province.

“Members of the government have made it very clear that they support abortion services as part of necessary health care in British Columbia, but those services are clearly not equally available to everybody in B.C.,” she said, citing the 26-hour journey from Haida Gwaii to Vancouver. “The cost of that travel is an incredible barrier.”

Though many abortion providers are unlisted to avoid harassment and stigma, they are often still available in rural areas — rural patients just need a point of contact with the health-care system to find one, said Dr. Regina Renner, a Vancouver Island obstetrician and gynecologist. In most cases, that would be their family doctor.

“Access can be improved — for example, in rural areas or communities that do not have enough providers,” Renner said. “This has become a greater concern with an increasing shortage of family physicians who otherwise might have been the first point of contact for patients.”

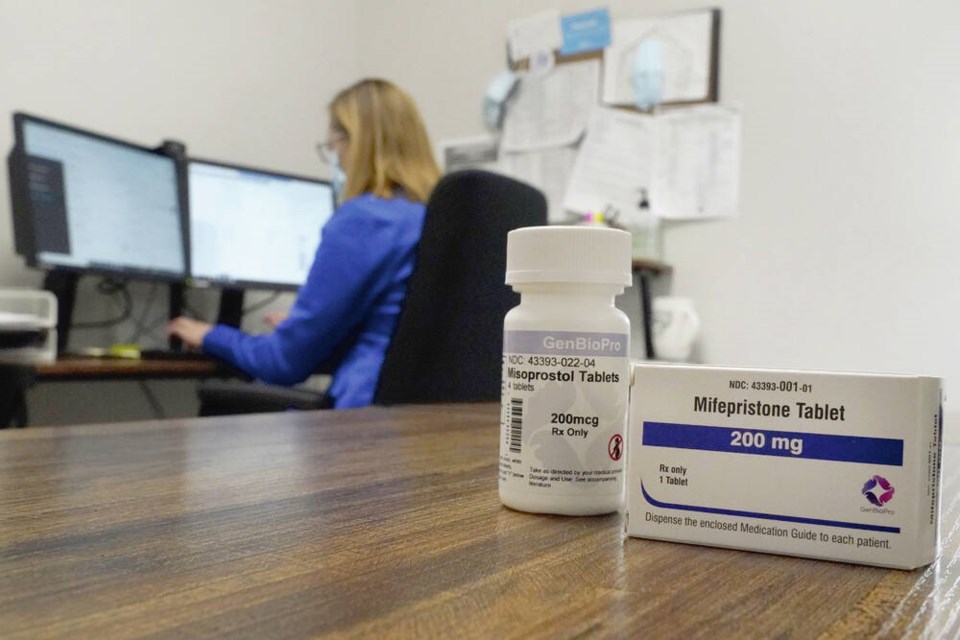

In 2017, the abortion pill Mifegymiso, a combination of the drugs mifepristone and misoprostol, became available for pregnancy termination up to 10 weeks. Renner contributed to a 2019 survey of 388 Canadian abortion providers that found first-trimester abortions represented 28 per cent of all pregnancy terminations that year. More than half the providers were family doctors, and almost all of them used the mifepristone/misoprostol regimen.

The study concluded that since the arrival of the abortion pill, there had been a significant improvement in access for rural and other under-served communities.

Renner said Mifegymiso significantly changed abortion access across the country, but noted that in most cases, patients still need to see a doctor. Telemedicine — which saw an upswing during the pandemic — could eliminate that barrier, but there are limits. Patients might require an ultrasound, which isn’t always readily accessible and could require travel or time off from work.

“There’s definitely some patients who would need an ultrasound to confirm gestational age, because they might not be certain, or it’s the provider’s preference to confirm how far along [in pregnancy] the patient is,” Renner said. “Telemedicine is something that can hopefully be further expanded.”

Dr. Ruth Habte, a UBC resident doctor in obstetrics and gynecology and a member of AccessBC, which advocates for free prescription contraception, pointed out that a lack of anonymity can also be a barrier in small communities.

“The more rural locations you go to, everyone kind of knows each other. If you’re really good friends with the pharmacist … and you don’t want them to know about this thing you’re going through, then that becomes really difficult in terms of privacy,” she said. “It’s also possible that the pharmacy will choose not to carry Mifegymiso.”

And abortions are only one piece of full reproductive health care, added Habte, who wants to see free and equal access to all birth-control options, including Intrauterine Devices (IUDs), which can cost anywhere from $100 to $350.

“It’s not only important to have a variety of options available to people, but also making sure those same rural areas have care providers that can insert IUDs, who are capable of prescribing any birth-control pill the person is eligible for and interested in,” Habte said.

Abortions and birth control go hand in hand, she emphasized. But the province hasn’t followed through on its 2020 campaign promise to provide free contraception.

“The contraceptive pill is the cheapest option by far — on a month-to-month basis, it can be $15 or $20 — but the chance of having a pregnancy even by missing one pill is quite substantial,” Habte said. “A lot of abortions are secondary to people not using contraceptives properly.”

The Pregnancy Options Line provides information, resources and referral for all abortion services, including counselling. It can be reached at 1-888-875-3163 throughout B.C. and 604-875-3163 from the Lower Mainland.