During the lockdown days of the pandemic, some folks took up a new fitness routine; others taught themselves to knit or make sourdough bread.

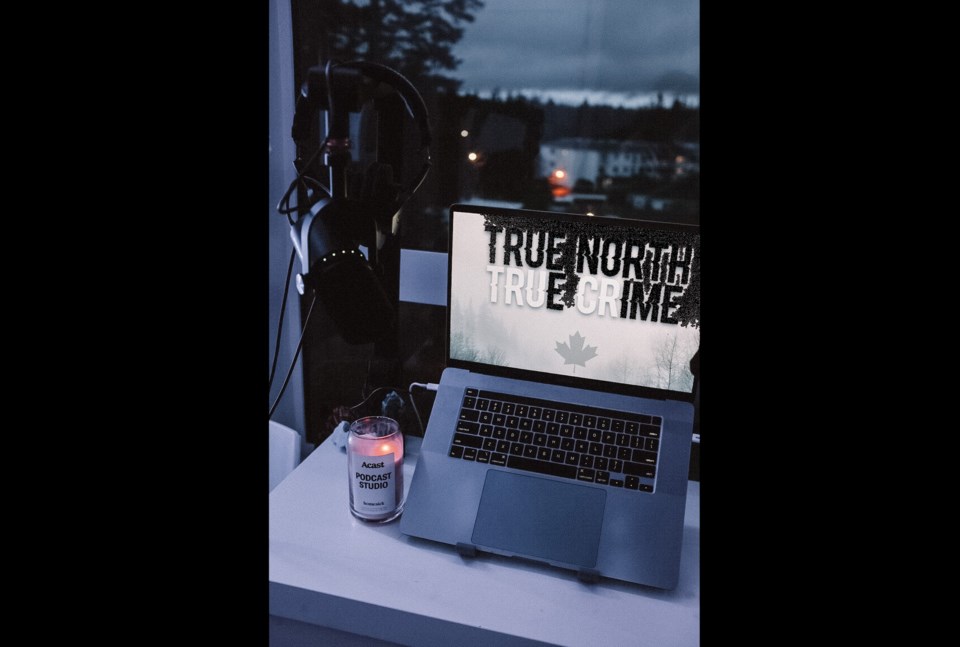

Caitlin and Graeme, a couple based on Vancouver Island, launched the true-crime podcast True North True Crime.

(Because the nature of their podcast puts their safety in jeopardy, The Squamish Chief has agreed only to use their first names.)

If you follow Canadian true crime podcasts, you have likely heard them. Since they launched in 2020, they have produced 46 episodes and amassed 1.5 million downloads.

They focus on a diverse array of B.C. and Canadian cases, often at the request of the victim's family.

The Squamish Chief caught up with Graeme after the pair had just dropped the Madison Scott episode, about the 20-year-old who attended a party at a campground south of Vanderhoof on May 27, 2011, and never came home.

What follows is an edited version of that wide-ranging conversation that delved into the creation of the podcast, the cases they cover, and why.

What is it about true crime that drew you to it?

I've always had a healthy appetite for understanding the facts of why things happen — and what causes them.

With our podcast, we'd never do, you know, inside the mind of a mad person or inside the mind of a serial killer. We're not interested in that. We're interested in the causes and conditions that create the environment for a crime to happen, starting with the person's life, and then moving backwards, moving out.

I also lived in Victoria for a long time. I was around for the disappearance of Michael Dunahee (1991), Darren Huenemann setting up his mother's and grandmother's murder (1990), and Reena Virk's murder (1997).

So oddly, Victoria was a real hotbed for a unique kind of crime that was sometimes youth-driven. And so, I had a healthy fascination for wanting to understand why those things happened.

What have you learned about how the justice system works through these cases?

With a case like Natsumi Kogawa, who was killed by William Schneider, he has admitted to the murder. And now he's going through the Supreme Court with appeals and winning. I realized that Kogawa's family, who lives in Japan, is being further victimized by the Canadian justice system, as a result of Schneider's Charter rights, which do exist. It is interesting with the criminal justice system that sometimes we will see what we think is justice being meted out, but then it actually doesn't because of the parole and the appeal process.

That's why when we do cover murders that are already solved and have gone to court, we tend to cover ones where we want the audience to be able to ask the question, "Was justice served?"

What are some of the other takeaways about the system you have learned?

In restorative justice, there is the participation of the victim, the offender and the community. Whereas in our criminal justice system, there's the participation of the offender and lawyers, and possibly, a jury, but sometimes there's a judge trial.

The victim is actually one of the last voices to be heard. Victim impact statements only started being a part of the court system within the last decade. And they're primarily used for sentencing.

[The Canadian Victims Bill of Rights came into force on July 23, 2015. This act gives every victim the right to present a victim impact statement.]

I believe we erased victims from the court system. And I know that the Crown prosecutors do their best to represent them, but really, it comes down to an agreed-upon statement of facts.

Some true crime can be very sensational, but yours is very victim-centred, and often you work with families. Did you set out an ethical framework?

We did have a talk to establish our values as a podcast before we got into it. And we both really liked the idea of "Primum non nocere," the Hippocratic Oath — first, do no harm.

It's a goal to make sure that what we're doing is not sensationalized and doesn't take advantage of people who have already been taken advantage of. And that we are not centring offenders in the story.

We have also pushed away from giving our opinions and also from talking about ourselves.

We just tell the facts of the case.

The cases you feature are very diverse and most are not very well known. How do you approach choosing cases?

Diversity in Canada comes in many forms. First, there's geographical diversity. And you know, in our first few episodes, we really started close to B.C. because that's what we knew. But Canada is a giant country with a lot of people in it. So we needed to bring in geographical diversity, but we also really prioritize amplifying those voices that aren't being heard. Sometimes there will be a case that gets a few minutes or two on the news, and then it is gone.

And that's fair; that's just the nature of news.

But with the podcast, we have a unique opportunity to present a 35- or 50-minute deep dive into the case. That allows family members to tell us who this person was. So we want to find those cases that are less spoken about or that have fallen to the wayside — such as with Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG), and also missing and murdered Indigenous boys and men.

We look at the stories through several diversity lenses, whether it's geography, socio-economic situation, gender-based violence, mental health, addiction, race and ethnicity.

Through the podcast, you see close up that a lot of really awful stuff happens in life. How do you do a story and then go and have a bagel and a coffee?

Caitlin is very good at it. She's very empathetic, she's very caring. She's very understanding in the moment; when we're listening to the audio of a family member, she will cry, or she'll see the injustice of it all, and then she'll be fine afterwards.

Some stories do haunt me. The story of Lise Fredette who was 74 years old, and murdered by a man who was stalking her in Peterborough, Ont., there's a moment when I was speaking to her adult son when he says, "I saw her walk down the driveway and that was the last time I saw my mom." And, honestly, that audio played in my head every day for weeks.

I do have a history of working in social work, and I still continue to work in that world. So I'm also able, in the moment, to be one-on-one with the person — I'm there for everything that's happening. But I'm also able to compartmentalize it and say that was then and now we have got to move on — to keep our goal in mind. But at the same time, I do highly recommend therapy.

It is a heavy thing. But your podcasts really could bring help to some of these families.

Yes. Out of our cases, there's Cory Westcott, missing out of Nelson, B.C. His mom ended up getting connected with Please Bring Me Home after our podcast.

With Geraldine Settee, one of the oldest unsolved MMIWG cases in modern Canadian history, a retired police officer agreed to help the family out after our episode. And then Teaghan Coutts, who was abducted by her grandparents and taken to Turkey, she ends up home, and I think we were the only podcast to cover her case. I know there was a lot of work that went behind the scenes — we clearly didn't solve the crime — but we helped by being an incremental part of the conversation.

There are literally millions of podcasts out there. Have you been surprised by your success?

Yeah, absolutely blown away. ... We walked into the podcast space in 2020, during a pandemic, when everybody started a podcast.

We stumbled and fumbled our way through those first episodes, and then we had friends like bigger podcasts like Generation Why True Crime Podcast, out of Kansas and Michael Whelan does Unresolved out of Alaska, and of course Kristi Lee, at Canadian True Crime who were so kind to us and gave us shout outs.

We kind of kept using those moments as confidence boosters to continue what we were doing.

And then, in the summer of 2021, so a year after we launched, we began to see some growth. And we were approached by Acast to become part of their Canadian network.

If local families want to reach out to you, how do they do that?

There are a couple of cases in Squamish that we would like to help amplify if there are people out there who want to talk to us about them. We would be interested in doing another deep dive into the Marshal Iwaasa and there's the historic case of Kathleen Vauden Kermode and the missing man, Daniel Reoch.

To reach the podcasters, email [email protected].

Find the podcast at https://linktr.ee/truenorthtruecrime.