I was recently telling someone about how much I loved my two stints as editor of the Undercurrent.

“If you loved it so much, why did you leave?” she asked.

Why, indeed.

Both times I felt wrested away from an island and a newspaper that fulfilled so many things I crave: connection with community and a feeling that what I did had meaning.

The first leave-taking was my bosses’ idea. They asked me if I’d be interested in becoming the editor of the now-defunct North Shore Outlook in the sly way bosses often have: they pose it as a question but really they’re telling you that this is what they need you to do.

The second time it was breast cancer. I thought I’d be away for the month it would take to recover from a mastectomy but it turned out I also needed chemo and radiation. When my year of treatment and recovery ended, I was asked to become the editor-in-chief of the Vancouver Courier, which is where I met the very smart and very passionate Bronwyn Beairsto. The Courier internship was her first journalism job but, as many islanders have since discovered, she had that spark that convinced us she’d be the perfect steward to guide the Undercurrent in its next iteration.

And now, life has wrested me back to the island.

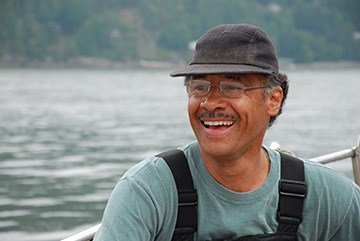

My husband, Jean-Edouard de Marenches, died in September. He had successfully overcome cancer twice and when his lymphoma returned last December, he put every ounce of his formidable resolve and courage into trying to find new ways to outwit it. He had so much living left to do.

I met Jean-Edouard when I was a young reporter starting my career at another small-town paper, the Haliburton County Echo. He and his family had purchased an old hunting and fishing lodge on the edge of a lake in Ontario’s cottage country and transformed it, and the surrounding forest, into an amazing property. Guests could spend their day “mastering the art of doing nothing… beautifully” and reward their commitment to a life well lived by enjoying a fabulous meal prepared by chefs from France.

We both had jobs which consumed us — often in very positive and rewarding ways. Twelve years ago we decided to try something new. We settled on Vancouver and I was blessed to get the job on Bowen, commuting to work every day on the water taxi. After 25 years of being together, one of the first things Jean-Edouard and I did was get married on the upper deck of the Queen of Capilano.

Bowen became our grounding place in a way our downtown condo never could be. Islanders were so open and welcoming. Friendships were quickly made and we were astounded by the vibrant social life that exists here.

Just before my husband and I met, he had crossed the Atlantic by sailboat. When he found himself looking out onto the Howe Sound, he knew he had to return to the water. We bought a sailboat, which we kept at Union Steamship marina. Every time we drove down the hill towards the ferry terminal at Horseshoe Bay, we felt we were about to be transported to another world. Then, when winds proved too fickle, we traded the sailboat for a Grand Banks, using Bowen as second home, as well as a gateway to explore the coast.

In 2018 my husband’s cancer returned. Its main impact was extreme fatigue. We decided I would retire, especially since it was getting harder to pretend that I could devote the level of focus that being a newspaper editor required. With my husband’s energy waning, we sold the boat, severing a physical tie to Bowen Island.

And then the pandemic happened. Each generation experienced its hardships and deprivations differently. For my husband, who was in his early sixties, it was the frustration of being cut off from a retirement that he had worked so hard to achieve as well as the sense that he didn’t have many years to sacrifice to being homebound. When the medication that had fended off the cancer’s return suddenly stopped working, it was a cruel blow coming on the heels of a cruel year.

My “journey” — I dislike the word but it is indeed apt — through those 10 months was parallel to but different than his. One of my quests was to find meaning in it all, searching for anything that could sustain me. That led me to reading Man’s Search for Meaning by Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl. The deprivations and determined dehumanization that he and other concentration camp inmates endured defies all understanding. As he describes those years, and how he kept his psyche intact, I took from him the message that when we are faced with circumstances we cannot change, the only thing we can do is change the way we deal with them.

That’s how in my mind I was able to try to switch the focus of my awareness. Yes, I was watching my vibrant, immensely intelligent, dreamer of a husband fade away beside me. I couldn’t do anything to stop the insidious cancer cells bullying their way into his life-sustaining bone marrow. But I could help him create an atmosphere of love and quiet fortitude. And that’s what we did.

I also vowed to say yes. Yes to new experiences. Yes to travel. Yes to former publishers who ask if I could help out during the transition between editors at the Undercurrent. I love being back on Bowen, truly I do. However, this time I am more at peace with the thought of leaving it when my month is over. Life beckons.

I cry as I write this. I know I will cry at Bowen Island’s Remembrance Day service. It was on Nov. 11, 2009 that Jean-Edouard and I drove down the Sea to Sky highway for the first time, passing by Bowen Island’s night-shrouded silhouette as our cross-Canada trek to an exciting new life in B.C. approached its conclusion. I’ll cry for him. I’ll cry for all the Viktor Frankls and all the men and women who fought against tyranny. I’ll also cry for those who, caught up in battles beyond their control, discover humanity’s innate ability to endure.