It’s not everybody who gets a personal invitation into a palace, but one island resident, Andrew Todd, has been invited to into royal settings more than once.

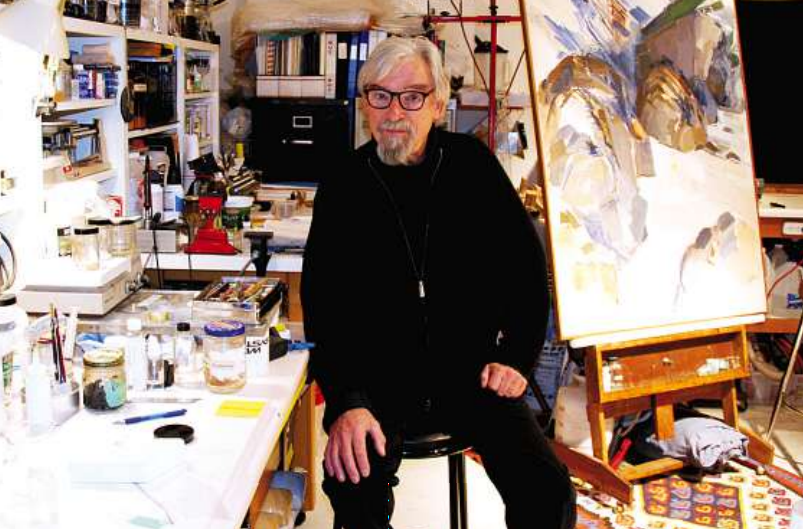

Todd is an Art Restorer with decades of experience under his belt. Over the years he has been brought to museums, galleries, first nations settings and palatial homes to rescue or assess, works of art in need of repair or preservation.

Two years ago, the Canadian Embassy in Greece invited Todd to Athens. At the time, more than artwork was in need of repair in Greece. Todd recalls being set up in an apartment overlooking the Acropolis, but being unable to set foot outside because of the tear-gas that ate it’s way into the air passages of the building in which he was stationed. Though the streets in many parts of the city were in chaos, Todd says that he managed to stay on task and restore a Canadian totem pole that had been given to the Canadian Embassy in Athens in the early 70’s. It was badly eroded and was moved to a museum where Todd worked on the restoration. While he was there Todd staged workshops for peers, and demonstrations for the public.

Todd admits to enjoying the privilege of getting to explore museums without the crowds. One particularly interesting experience he says, in when two curators in Istanbul, Turkey, escorted him into Topkapi Palace Treasury.

Topkapi Palace had been home to The Ottoman sultans for four centuries. One curator had the key to unlock one door, the other could only unlock his assigned door. Todd was lead through the palace to a locked display case with a throne. One of the curators opened the case and Todd began assessing the condition and restorative action needed for the gold-plated throne. The throne ”had emeralds encrusted that were this big,” Todd says, holding his thumb and finger apart indicating the space of a couple inches. The sultan’s throne, decorated in giant emeralds and pearls, had been a gift of from a Persian ruler in the 18th century.

Windsor Castle is another palace where Todd has worked. The restorer spent a portion of his summer two years ago at Windsor Castle assessing a totem pole carved by one of Canada’s leading West Coast First nations artists, Chief Mungo Martin. The pole is in the Queen’s Private park that Todd says is “around the size of Bowen.” During the time Todd was doing the restoration he was given a tour of the grounds and he say’s he got to see palace life “from the point of view of people who live there.” Todd spent his time doing substantial scientific testing of the sculpture before coming up with a proposal for conservation of the totem pole.

With Todd, he takes on so many extraordinary projects, he has to be prodded to remember all the different places and items. Todd has restored Emily Carr ceramics that had been shattered, as well as a one metre-tall sculpture carved from serpentine stone in the Winnipeg Art Gallery. While the art was in storage it fell over and broke into hundreds of pieces. Todd was called up to seamlessly fit the pieces of the sculpture back together. Todd says that there was a fair bit of finger-pointing and tension between departments at the museum after that disaster, but it had happened because the foam the sculpture had been placed on had not compressed evenly under the weight of the stone. This set it off balance causing it to tumble off the shelf and shatter.

Todd was also called to Toronto to the Royal Ontario museum when what was said to be “the ossuary of Joseph” was accidentally cracked. For Todd, he was oblivious to the media fuss over the ossuary. All he saw was a piece of antiquity in need of restoration.

“The downside” to getting private access to museums and artwork says Todd, “is that I get to see what is stored in basements; -- acquired during oppressive times.” He says that “when all these works of art come out,” it’s piecemeal as opposed to a socially coherent exhibit or story. Todd points to how Greece has been trying to get the Elgin Marbles from the British Museum “but they won’t give them back.” Similarly, when it comes to First Nations art,

“Things were lifted right out of villages when they (the villagers) were out fishing.” As a curator he sees the artifacts that never go on display. ”There’s a shrine from Friendly Cove, (on Nootka Island, BC,) --it was removed from the village fully intact and has never been exhibited. It’s in storage at the American Museum Of Natural History.”

Todd says that because of his west-coast home base, his work now focuses on restoration of First Nations art, and in particular, totem poles. “I studied conservation from point of view of wooden artifact world but got out here carved wooded stuff is everywhere.”

He adds, “I’ve worked on all the pieces in Canada Place,” and every year, he restores a Vancouver totem pole carved by Bill Reid. If you ask Todd about his most interesting work, he’ll say “totem poles. --Some of them are fantastic works of art.”

Regarding art back home, and specifically public art on Bowen, Todd says he doesn’t “get involved.” Todd says he likes art that is inspiring. Public art, in particular, “should make you think.”

The mild-mannered Todd has a few things to say however, about the totem pole created by a Tshimshian first nations artist lying on the ground in Horseshoe Bay. “Oh god,” he mutters. “That’s awful and I’ve told them,” he says, referring to the District of West Vancouver, who have laid a deteriorating totem pole down on the ground, leaving it to decompose. Dogs pee on it and people sit on it, wearing off the paint. “That’s a big mistake,” says Todd. “The artist is no longer alive and West Vancouver feels the cost of preserving it is too high.” He adds that there is a bit of tension between the Tshimshian nation and Squamish who want their own pole. In any case, West Vancouver has posted a sign at the pole saying that allowing a pole to decompose is a native tradition, ”That tradition is highly questioned,” says Todd. Todd points out that in the late 1900’s the missionaries in Massett tore down the poles and lay them as roads. Poles weren’t preserved by the first nations “because they didn’t have resources;-- but to carry that forward as a tradition doesn’t make sense.”

Todd says he can’t necessarily decode or read the story being told in a totem pole in spite of all his time among them. “They are all complex and different.” He says the totem poles are both the most challenging and interesting work and for him, it feels like something with a bigger meaning than just a piece of art. “There’s an artistic complexity, it’s a story-telling, language, so you are working on more than the physical material, it’s the preservation of legends.”