How do you film a raid of slave raider ants coming into another colony, stealing babies to bring home and use them as slaves? That’s the sort of thing Jeff Morales struggled with as a documentary filmmaker for National Geographic while doing a special on social insects.

His crew solved the problem by creating sets designed to allow for lighting and camera angles while making a space where the insects would “be comfortable and behave normally.” This sort of challenge is ongoing for the man who has won numerous awards for his groundbreaking work in documentary filmmaking.

Morales says that one of the big moments in his career was producing his first film, which happened to be about giant hornets in Japan called “Hornets from Hell.” As a man with great respect for invertebrates, he says the name was “tongue in cheek,” adding “It was my first gig running the show; my vision. I took a lot of editorial risks. But high risk, high reward,” says Morales.

The hornets Morales was shooting “were 3 inches long. When I first encountered one, I almost felt it before I saw it. “ He describes how, when they fly over the ground, “the dust blows away like it does for helicopters, and there’s this clicking sound because they click their mandibles when they move.”

Like characters in a science fiction movie from his childhood, the hornets spurred Morales’ imagination. “I thought I’d do an homage to sci fi films that I liked as a kid, infusing it with science, arts and culture. It was tricky.” Morales chose to live alongside these creatures, necessitating that the crew don protective suits because the insects “had a stinger that can dissolve tissue.“

Morales and his crew based themselves in a cabin with the hornets, in the mountains of Nagano. In order to film closeup views of the life cycle of the insects, the crew built sets which would become the early season nest site for the hornets once they had introduced a queen to the set. “It was a huge challenge” but the team had an “amazing researcher and a cinematographer” who did macro work for the BBC and who became a mentor to the rookie producer. “He gave me the confidence to run with crazy ideas.” Hornets from Hell was a huge success. “We drew the audience in and then showed how amazing the hornets were, turning it on its head. –

“That’s one thing I really love about this job. You become a graduate student for every subject you work on. You are able to get amazing access the leading researchers on the planet and get a window into the lives of animals and locations. “

Morales and his wife Kimwere both working for National Geographic, living in Washington, DC, when he had a chance to work on a film, Edge of the Sea, based in Bamfield, on Vancouver Island. He was “the low man on the totem pole. I was everyone’s assistant,” which Morales says was a great way to learn from all the different areas of expertise. He says that it was in Bamfield that he knew conclusively that Canada’s west coast was where he wanted to be, and that being a cameraman was unquestionably what he wanted to be doing with his life.

Rudy Kovanic, a highly regarded filmmaker that Morales assisted, invited the novice to Bowen. “I fell in love with this part of the world,” says the man who has spent a lot of time in some amazing places. Bowen has been home for the Morales family for a decade now and the filmmaker continues to feel passionate about the area. Morales says that he would still love to tell the story of this region, incorporating the natural history and culture and “looking at the behaviors that inform the legends; there are remarkable stories to tell.”

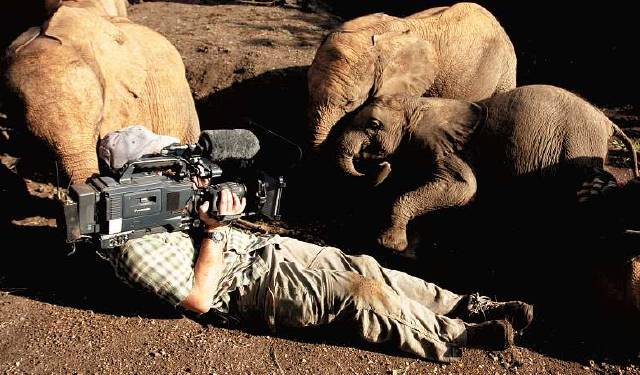

On any shoot, Morales immerses himself in the local community, both human and animal, trying to capture the essence of the culture. One of Morales most profound experiences occurred while living among the elephants at the Sheldrick elephant orphanage in Kenya. “There’s something different about the elephants. When you look them in the eye, you know there’s a deep intelligence. “ Morales describes his time with the elephants as being very privileged. “I was literally on the ground with them and spending time with people who spend 24 hours a day with them. I saw the dedication of the handlers and the emotional aspects of the elephant rescue efforts.”

He was on site long enough to see the orphans when they were being rescued and at their lowest state, to the transformation as they were brought to a safe and nurturing place to recover with the keepers and other elephants. ”They were like kids, each with their own personalities. One would be cuddly, another was mischievous and there was a bully. They’d all want to play but, playing with a 500 lb animal, I got bowled over lots of times.“ Eventually the orphans got moved into a stockade where they start to interact with wild elephants and other orphans who had transitioned into the wild. “It’s hard to imagine how someone could murder the family for ivory.” He is passionate about the need to protect the elephants, but, he adds, “I can see it because they are destitute,” referring to the poachers. “I’m very privileged. I never lose sight of that.“

He holds onto to hope for change for the destitute and the elephants and hopes that maybe his work can help to show the animals in a different way to those that would otherwise treat them with casual indifference or destruction. Though he says he has never encountered any threat due to political unrest or criminal activity to do with animals, he says that when they went out to an orphaned baby elephant being rescued, they had armed escorts. The team found the baby in the heart of poacher territory. ”That’s when I noticed that a perimeter of men with AK47s” were keeping the crew safe.

What may be surprising about Morales is that his passion lies with the invertebrates. He talks about wanting to go back to Bamfield and Barkley Sound and remake Edge of the Sea in high definition. He says that it’s hard to sell the idea of invertebrates as opposed to the big animal stories. “I have something of an affinity for the invertebrates. They are the animals no one really appreciates.

Morales has been producing Wild Canada over the course of two years for The Nature of Things sesquicentennial, 2017. It’s a huge production, touted by the CBC to be “the largest natural history survey of Canada in our generation -- filmed across the country, showing animal behaviour never before captured.” Morales has just shot the fall segment, and is taking stock of what’s in hand

Jeff says it’s a luxury to have the kind of time he has for Wild Canada. With otherwise short time lines, a filmmaker is often backed into a corner, having to make a decision as to whether or not to wait for a shot when the weather or animals don’t do what the team had planned around. Days cost dollars, which are in limited supply. Sometimes they have to walk away from a story.

Morales says that in the last couple years he has seen less predictability with weather and seasons. Scientists have the data, have studied the subject for decades and normally would be able to reliably predict behaviour of animals. “It’s been pretty loopy the past couple years.” We hear a lot more from researchers that things are happening later.”

Morales feels strongly that scientists benefit from being able to tell their own stories instead of waiting for a documentary to be made. Because of this, he has started teaching filmmaking courses for researchers and scientists. “One of the highlights of the job is that I also work with knowledgeable executives, camera people, and researchers. It’s a collaborative process. Always a group effort.”

The toughest part of Morales’ job is going to the airport. “I hate travelling now,” he says, adding that he’s fine once he’s on task. What he hates about travel is leaving his wife Kim, and three teens, Finn, 18, Luke, 15, and Stella 14. He managed to bring Luke, along to Florida to be on site for a show on sea turtles. They spent a long night on the beach and “Luke became a crucial part of the crew.” Morales makes it clear that his job “is not glamourous. It can get boring or frustrating, but,” he adds, “it was pretty cool to get to share that time.” Finn has also been on shoots, and Stella’s turn is coming.

As for the future, he “wants to have a positive outlook. In the field I’m encountering dedicated passionate and talented people and it makes me hopeful. “ He pauses, ”I’m hoping the people making the big decisions will catch up.”