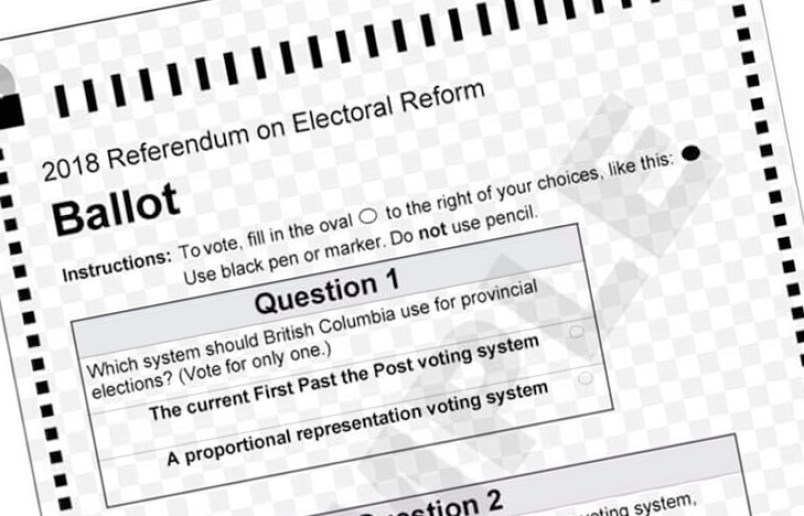

Next month, Canada Post willing, British Columbians will be voting on whether or not to adopt a new way to elect our provincial government.

One of the main arguments against our current “First Past the Post” (FPTP) system for electing members of the legislative assembly is that it regularly gives a majority of the seats in the legislature – and therefore 100 per cent of the power – to one political party that usually gets well under 50 per cent of the actual votes in the province.

But it seems to me that isn’t the fault of the voting system we use. The problem, rather, is the corruption of our parliamentary system of government, and the way it was actually meant to run.

The principle of responsible government, developed in the Parliament of the United Kingdom and adopted in the 1840s in Canada, means that the government of the day is responsible to the legislature, whose members are responsible to the people who elect them. If the government does not have the support of the majority of the elected members – or in the beautiful old-fashioned parlance, “command the confidence of the House” – it must either resign and either let another government have a try or call for an election.

But that didn’t mean a government had to resign any time it lost a vote. Traditionally, the only automatic “confidence votes” were on the budget and the government’s agenda (the Speech from the Throne). The government could designate other votes to be “matters of confidence”, but it wasn’t a given that a member on the government side would have to vote on the government side for every single measure.

Historically, this led to a balance of power between a government and its elected members. An ambitious legislator who wanted to be part of the government had an interest in supporting the leader of the day on confidence measures, but that leader also had to keep its individual members happy and on side because the government’s power came from them, and members still had latitude to vote with or against the government on some matters.

That meant the individual you and I elect directly had a lot more power to vote his or her conscience, as well as to change leaders or even change governments.

But as political parties became more cohesive and better organized, they became stronger, upsetting that balance of power. That means that when you cast a ballot in last year’s provincial election, you might have been voting for the actual person whose name is on that ballot, or you might have been voting for that person’s party or its leader. But if you liked Todd Stone but not Christy Clark, for instance, you had a difficult choice to make.

Meanwhile, governments of all stripes got into the habit of making every single vote a confidence vote, making it much harder for individual members to vote their conscience without risking an election.

Those two factors have made the power of the individual MLA – the person whose name is on the actual ballot – significantly weaker.

How could this happen? Mainly because a huge chunk of how our government actually works – all the stuff I just described above – isn’t actually written down. Our system of government relies on convention, and that tradition has become gradually corrupted.

That’s how a vote for a person to represent a small portion of the province becomes a blank cheque to a totally different person to run the whole province for four years at a time.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Look at the House of Commons in the UK – the system ours is supposed to be based on – where individual elected members hold significantly more sway over their party leaders and where policy can actually be influenced and shaped by individual members without risking an election.

Fix those issues, and you fix the problems that FPTP is tagged with, without losing the most important thing – the connection of local representatives to the provincial government.

If we move to a system where elected representatives are unmoored, even partially, from the communities they are supposed to serve, we lose the underpinnings of responsible government.

I’ve indulged in a lot of political science nerdery here, but let me put it more simply. Imagine if you drove a car that’s designed to run on 10W30 oil, but for years you’ve been putting 0W20 in it and as a result, it’s not working properly. Do you change the oil, or replace the engine?

That’s the question we’re facing here, I think. Let’s vote no to fixing the wrong problem, and get on to fixing the real problem.