The history of British Columbia’s Agricultural Land Reserve (ALR) began in Richmond in the early 1970s when Harold Steves and other local farmers noticed that prime agricultural land was being sold off at an alarming rate. Seeking to protect farmers and farmland, Steves, a former MLA, became the driving force behind the Land Commission Act of 1973, which established the ALR.

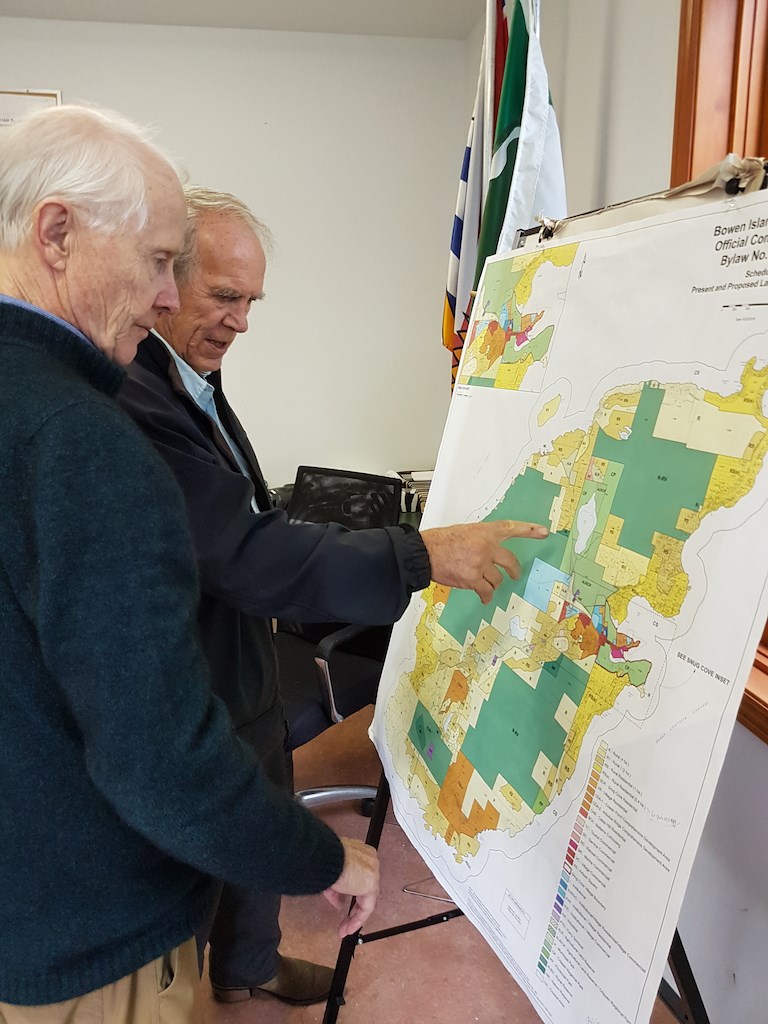

Last October Steves, who is often called “the father of the ALR,” was invited to Bowen Island to lead one of the municipality’s Climate Conversations.

Steves began by talking about his Bowen connection. His family lived on Bowen in the 1800s and his grandmother, Bonnie McElhinney, taught school here in 1894. The Steves family’s farming legacy in B.C. can be traced back to his grandfather, Manoah Steves, who started farming on Lulu Island in 1877 and founded the province’s first seed company in 1888.

Fast forward to 1960 when Steves was attending UBC. He recalled that “we were already looking at how population and climate change would affect B.C.’s agriculture.” By 1973, he said, “B.C. was losing 10,000 acres of farmland per year to development and 28 per cent of the province’s farms were gone.”

After establishing the new ALR zoning designation that year, the Department of Agriculture was tasked with mapping the province’s agricultural land. They found that, although only 5 per cent of B.C.’s land was suitable for agriculture, a mere 2.7 per cent could support a reasonable range of crops.

According to a Vancouver Sun article dated Aug. 25, 1973, not everyone on Bowen was happy about the proposed ALR. Nonetheless, 182 hectares of Bowen’s 5,260 hectares were rezoned. Although opposed by some property owners, the ALR is now seen as one of the best examples of agricultural land preservation in the world. It is given credit for putting a halt to urban sprawl and setting the agenda for regional food security.

The same pressures that threatened farmland 50 years ago have intensified. In addition to climate change and a growing population, close to 50 percent of the ALR is not used for crops or ranching. One culprit is the spread of large estates on land where the owners have no intention of farming. This is a big issue in Richmond where the side effect is an increase in local property valuation. This raises the price of agricultural land and puts it out of the reach of farmers.

Kent Mullinix, of the Institute for Sustainable Food Systems (ISFS) at Kwantlen Polytechnic University, points to the need for revitalizing the ALR and reforming tax laws to make farming more economically viable.

A White Paper published by the ISFS states, “In this province, where farmland scarcity is so obvious, a diversity of large and small-scale agriculture importantly binds our communities and province together to provide any semblance of control over our food security and food self-reliance.”

The authors point out that industrial and energy uses of land are also whittling away our precious agricultural land resources. There is no place where this is more evident than the Site C Dam project on the Peace River in northern B.C.

Despite legal challenges by First Nations, environmentalists, and local landowners, the provincial government has decided to flood prime agricultural land to produce more electricity. It is estimated that the Site C Dam will end up flooding 6,469 hectares (15,985 acres) of which 60 per cent or 9,430 acres is prime agricultural land.

While there are ALR landowners who decry zoning that restricts them from subdividing and developing their properties, others are committed to preserving and expanding the ALR to increase food resiliency.

In the 2019, Bowen Island FoodResilience Society (BIFS) published two reports, “Toward a Resilient Food System for Bowen Island: An Agrarian Analysis“ and a “Communication and Engagement Groundwork Report” that Harold Steves endorsed enthusiastically, calling them “ … the best reports I have seen from agrologists anywhere, because they cover the wide spread of everything you could think about to resolve this problem.”

In the Agrarian Analysis, author Julie Sage writes that “Supporting the intent of the Agricultural Land Reserve is one of several essential components of a resilient food system.” In the report, she cites a BC Ministry of Agriculture 2011 land use inventory of Bowen’s ALR. Among the findings was, of the island’s 182 hectares in the ALR, only 17 hectares (9 per cent) was actively farmed (field crops, farm infrastructure, greenhouses).

When the survey was updated in 2016, Bowen only had 176 hectares in the ALR. Of those, 15 hectares (8 per cent) were actively farmed, as opposed to 20 hectares in 2011. Of the entire 917 hectares surveyed in 2016 (inside and outside of the ALR) 27 hectares are now actively farmed, as opposed to 34 hectares in 2011, representing a decrease of 26 per cent in farmed areas. Such is the fate of farmland in BC, including on Bowen Island.

No one knows this trend better that Harold Steves who continues farming in Steveston while advocating for farmland protection. Steves has held elective office for 50 years, as an alderman in 1968, an MLA from 1973-1975, and finally as a Richmond City Councilor. This year, Steves announced that he will not run for re-election in 2022.

The work that Steves inaugurated when the Agricultural Land Commission was formed is still urgent. Looking ahead, it will be up to us to create a robust food system. But first, we need to save the land from development and find incentives to support farmers.

For information on the reports mentioned, please email Bowen Island FoodResilience Society: [email protected].