The following narrative is what I remember from the end of World War II. I was four and a half years old so of course I do not remember dates and names, these were given to me in later years. But the images described here are the events and interaction with people is from my own recollection as I experienced them.

I was born in North Eastern Germany, in the Province of Mecklenburg, a farming country bordering on the Baltic Sea with hundreds of lakes, beech and pine forests, red brick houses and people with a good sense of humour and wisdom.

The village of Mestlin, to which our farm belonged, was on one of the most direct East-West routes used by refugees fleeing from the Russian advances. Looking through an upstairs window I remember seeing this endless stream from early morning into the dark of night. It must have started a year earlier, before I could remember.

My mother ran the farm for her father, who worked the family estate, about 60 kilometers away. My father had been in the Africa Corps, Rommel’s Army, and having surrendered to the Americans in 1943 was a Prisoner of War (POW) in the United States. My mother’s three brothers had died, two in the war and one sister committed suicide. Of their six children my grand parents had two daughters left and fourteen grandchildren.

We had a large farm house and sometimes thirty or more people stayed over night or a few days. It was in late March when relatives from Estonia had come to stay with us on their way West. Snow had melted and the muck in the farm yard was ankle deep for a youngster like me. I had shown my aunt the cow stable , when my boot got stuck. As I tried to pull my foot up, it slipped out of the boot.

My aunt lifted me up and began to cry unconsolably, holding me tightly. Later my mother told me that she had received news that morning of her husband’s death in France. She was twenty and he was thirty one years old. They had been married seven months.

Easter 1945 fell on April 1st. Our barns sheltered some 900 Russian POWs. The Mestlin Farm was ordered to shelter and feed them. Every day a horse or cow had to be slaughtered and hygiene had to be provided.

For all Christians Easter is the day when Christ’s resurrection is celebrated as the sign of ultimate redemption and forgiveness.

For Russians Easter is the greatest spiritual event each year, a time, when families unite. For those 900 men, brutalized by years of war, awaiting an uncertain future and without news from home, we, the children on the farm became the vision of their dream of home.

The commanding officer asked my mother whether the men could give us small presents they had made.They came and sang in a language I could not understand and the music was so different from the songs I knew. One song I remember began with a whisper and ended in a loud cry of pain and hope.

And then they pulled out the toys. There were tiny carved animals, Easter eggs, toys rich in Russian folklore.

I remember one man, he seemed old to me with his weather beaten face, unshaven, teeth missing, reeking of garlic and sweat, bending down, picking me up, hugging me and kissing me on the head, tears running down his face and sobbing. After he put me on the ground again, he reached into his pocket and pulled out what looked like a ping pong racket with a number of small carved hens mounted on the edge facing the centre. Under their tails strings were attached and knotted together underneath with a small weight. Through their feet were stuck small pins, which allowed the hens to rock, as if they were picking. The man placed the handle in my hand, put his gently over mine and began to move the toy in a horizontal circle. One by one the hens would pick and then raise their heads again as the weighted knot underneath rotated. In the calm position they had their heads down.

I have not forgotten the picking hens and the man’s face.

Much later I learned, that those Russian PoWs , more than 36,000, were handed over by the British and American forces and shot, because, according to Russian military law, to surrender or be taken prisoner was equal to desertion and punishable by death.

Shortly after Easter the Russians left, but the refugees needing help from us, increased. The news from the advancing Russian front must have been horrifying. I remember the screams of babies and so many faces and voices I did not know, day and night. I felt, that something dark, heavy and gloomy was approaching. Mother had less and less time for my one and one half year old brother and me. So I was put in charge when one of mother’s helpers could not look after us. I remember feeling abandoned and desperately looking for my mother.

Meanwhile, she was preparing the village and us to flee, to join the stream of refugees, if necessary. All motorized transport had been confiscated for the war effort.

But we had horses and each family in the village was given a horse, if they wanted to leave. People loaded a wagon in front of our house with important farm and family things. On the evening, before we wanted to leave (April 27, Hitler forbade anyone, who was not already on the road, to flee, because he wanted to bring any available troops to Berlin in a last effort to stop the Russian advance. To enforce this command, two armed guards were placed at the two main exits of our farmhouse. One was a fifteen-year old member of the Hitler Youth the other was a clubfooted man in his seventies. Both were armed and ordered to shoot.

That evening two ladies from mother’s school days stopped in to feed and rest their horses. Hearing of our situation, they convinced mother to pack the absolute necessities and climb onto their wagon early next morning.

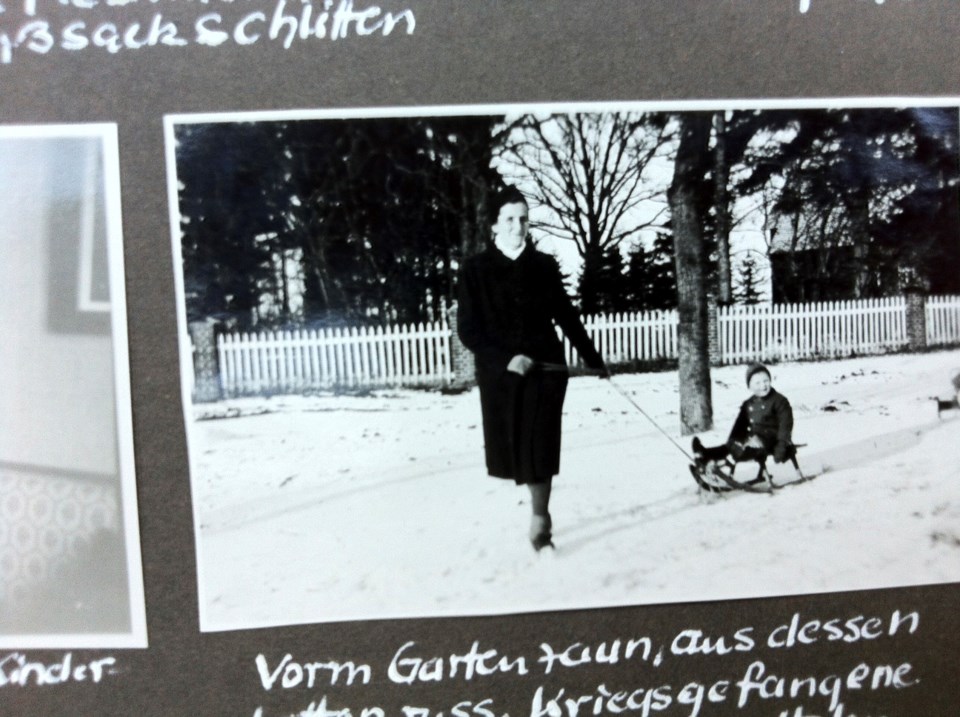

Before dawn we crawled out of a basement window undetected, mother carrying my little brother and I dragging a small suitcase. The farmhouse and garden were surrounded by a white picket fence. We slipped through a hole in the fence, where the Russians had pulled off slats to make the toys for us children. Hiding behind a hedge we spotted our friends’ horse drawn wagon and settled amongst several big crates. It took us an hour and a half to break into that panic driven endless stream of refugees.

Both sides of the road leaving the village of Mestlin were lined with mounds of all types of broken down transport and abandoned belongings.

Mid morning we heard the drone of aircraft engines. Within seconds they were upon us. Russian, English, American? We never found out. Mother’s friend, who rode the lead horse pulling the wagon, was able to reach a small forest. Thick branches gave us cover. As I looked across the country highway I saw a woman handing a small bundle to a man on the ground. I blinked for a moment. When I opened my eyes again I saw the two figures and the little bundle collapse in an explosion of blood. That same blast form an aircraft also spooked our horses so much, that they suddenly jerked forward and dislodged the crates. Between them our friends’ little dachshund was crushed. I can still hear his last gasping yelp.

Apparently, the air raid was triggered because German military units were using the same road, which made the refugees targets, as well. I heard screaming and yelling and saw fires. Ahead of us were several destroyed wagons, injured and dead people and animals. It took a while for survivors and helpers to make the road passable again, until the trek could continue to move.

After several hours of crawling forward, at about noon, we were stopped again. We had come close to the Stöhr Kanal, carrying waters out of the Schwerin Lake near Mecklenburg’s capital. At the Yalta Conference Churchill, Stalin and Roosevelt had declared this waterway as part of the boundary between the future Russian Zone to the East and the British to the West. Across it led one of the few bridges still intact. It was a drawbridge in two sections, one on either shore, which could be raised to let boat traffic through.

Late that afternoon it was our turn to cross. The bridge was so worn out, that the weight of the horses pulling our wagon pushed the half under us down. The horses spooked, but our friend reigning them from the saddle, was able to calm them enough to climb on the other half , bringing it down to an even level, that the wheels could roll across the crack without getting stuck. We made it. After a while the rider pulled over, slipped out of her saddle in utter exhaustion and walked back to the wagon. I saw my mother and her two friends hug and embrace one another and the horses were fed and given water …. and a few pieces of sugar.

That evening, about five hours later, the Russians reached the bridge and no one was allowed to cross anymore. It was April 28.

We by-passed the city moving West and reached my mother’s uncles farm late that evening. All of us, and the horses, had a few hours of rest. Some time after mid night we were on the road again, to avoid air raids. Traffic was light. At dawn we reached my grandparents’ estate, the house, where I was born. I ran toward them. I can still feel their arms around me. Breakfast was waiting and it smelled good.

The radio was switched on and the program was interrupted with sombre music and then a voice came on. I saw all the adults around me stiffen. After a moment my grandmother raised her hand and laid it on grandfather’s with words: “Finally, finally the monster is dead.”

Hitler had committed suicide.