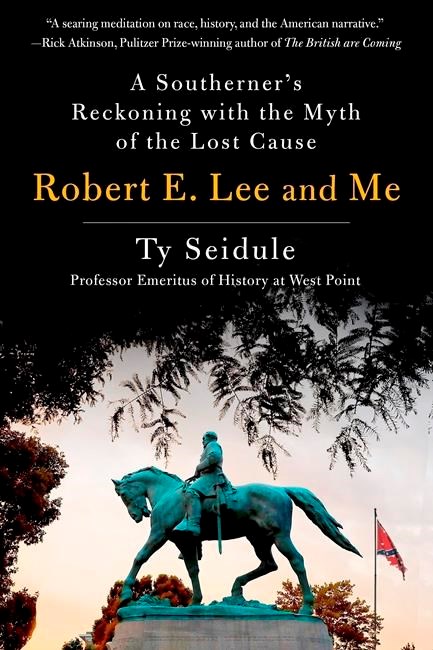

“Robert E. Lee and Me: A Southerner’s Reckoning with the Myth of the Lost Cause,” by Ty Seidule (St. Martin’s Press)

Few authors can say they have lived their story with quite the same authority as Ty Seidule, retired U.S. Army brigadier general and professor emeritus of history at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. He grew up in Alexandria, Virginia, and lived a life of white privilege provided by de-facto segregation. He revered Robert E. Lee.

Now, with the

Seidule’s book is particularly timely given the recent raid on the Capitol by hundreds of mostly white believers in an assortment of old and new myths. At least two of those who broke into the Capitol carried Confederate flags.

Seidule finished his book before the Jan. 6 insurrection at the Capitol, which made his research and writing even more soul-wrenching. In the Civil War, he writes, “the United States fought against a rebel force that would not accept the results of a democratic election and chose armed rebellion.”

Lee, still memorialized in scores of monuments, roads, counties and historical markers, was a traitor, Seidule writes, abandoning his oath of allegiance to the United States to lead the fight to preserve slavery.

Does something endemic in the American character render us susceptible to accepting beliefs unsupported by even feeble evidence? That’s a question for another book; Seidule has offered clear and compelling evidence, to our shame as a nation, that many of us remain unwilling to confront an American past that includes slavery, lynchings and embedded segregation that endures today.

Seidule’s book still has some chapters to be written — probably soon. Embedded in the 2021 military budget are directives to change the names of Army bases named for confederates.

And for whom should those based be renamed? Seidule has thought that out too.

In a Washington Post essay in June 2020, he recommends, among others, Vernon Baker, a Black lieutenant and Medal of Honor winner for his World War II heroism, and Charles Young, the third Black graduate of West Point. Young was forced to retire because then-President Woodrow Wilson didn’t want a Black man leading white troops.

The monuments and confederate names elsewhere also must go, Seidule writes, observing that otherwise they serve the same purpose as lynchings — to enforce white supremacy.

Seidule has written an extraordinary and courageous book, a confessional of America’s great sins of slavery and racial oppression, a call to confront our wrongs, reject our mythologized racist past and resolve to create a just future for all.

Jeff Rowe, The Associated Press