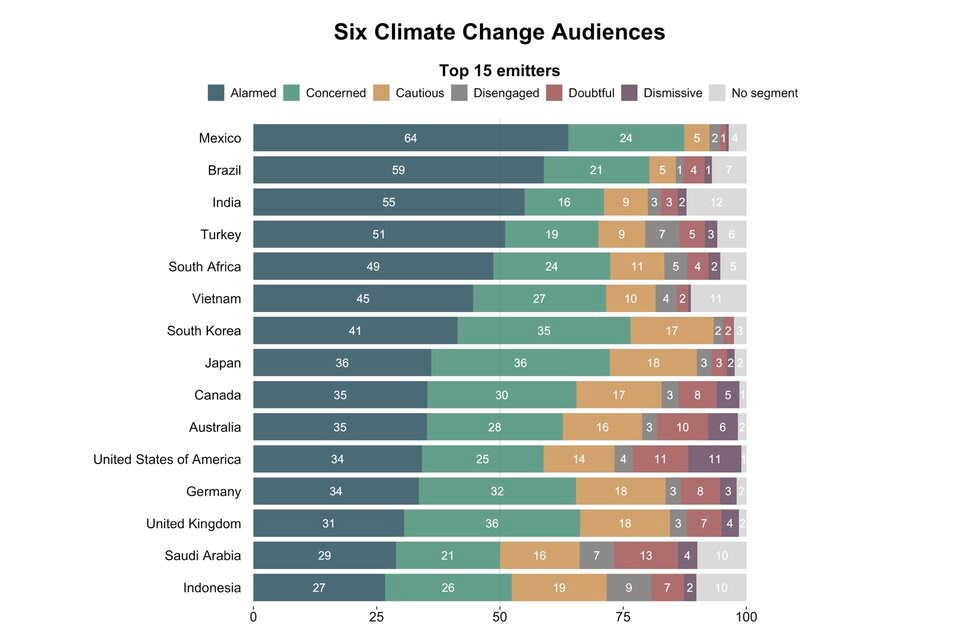

Among the world’s 15 largest emitters of carbon pollution, Canadians are the fourth most likely to doubt or dismiss the existence of human-caused climate change, a new survey has found.

The international survey, carried out by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and the social media company Meta, examined Facebook users’ knowledge, attitudes, policy preferences, and behaviour surrounding climate change in nearly 200 countries and territories worldwide.

The results show 13 per cent of Canadian respondents either thought climate change was part of a natural cycle or completely dismissed its existence. Of the big emitters, only the U.S., Saudi Arabia and Australia showed a stronger contingent of climate skeptics and deniers. The study did not include China, Russia or Iran.

Scaled down to North America, Canada had the third fewest respondents who expressed alarm over climate change. This group — both among the biggest emitters and in North America — was largest in Mexico, where 64 per cent of the social media audience said they were convinced climate change is happening, human-caused, and an urgent threat. Those who were alarmed by climate change also strongly support climate policies.

“We find that the Alarmed are the largest group in about three-fourths (80 of the 110) of the countries and territories surveyed. In fact, half or more respondents in 29 countries and territories are Alarmed…” wrote the authors in a summary of the results published Tuesday.

South America was found to have the greatest proportion of countries (two-thirds) with a majority of alarmed respondents.

Globally, Chileans (65 per cent) were found to be the most alarmed by climate change, followed by Mexico (64 per cent) Malawi (63 per cent), Bolivia and Costa Rica (both 62 per cent), and Sri Lanka (61 per cent). In Canada, however, only 35 per cent of those surveyed reported being alarmed by changing climate conditions.

The data was gathered in the spring of 2022 from nearly 109,000 active Facebook users 18 and older took. Of those, 1,026 were from Canada. Potential respondents were given an invitation to participate in a short survey at the top of their Facebook News Feed.

As misinformation 'runs rampant,' a warning about artificial intelligence

Undermining well-established science has always been more complicated than a straight lie. Suppressing its own scientific findings was only part of ExxonMobil's multi-decadal fight to undermine the role burning fossil fuels has had on the global climate system.

Today, misleading information surrounding climate change remains a significant hurdle to effective policy around the world, a growing body of evidence has shown.

Climate misinformation (when people inadvertently share false information) and disinformation (intentionally sharing false information) have spread so far that in many countries the majority of the population has been duped in some way.

A 2022 global study from Climate Action Against Disinformation (CAAD) showed between 55 and 85 per cent of people surveyed believed at least one climate change misinformation statement.

The study, which said climate misinformation “runs rampant,” found at least a quarter of people surveyed across India, the United Kingdom, United States, Germany, Australia and Brazil believed that their country “cannot afford to reach the target of net zero emissions by 2050.”

Mis- and disinformation can take on many forms. Sometimes it occurs through the omission of data or by cherry picking information to suit a narrative. Whether intentional or not, false information on climate tends to erode trust in science, institutions, experts and their solutions to dig humanity out of the spiralling impacts of human-caused climate change, CAAD says.

Last month, a report from Sweden’s Stockholm Resilience Centre warned the rise of artificial intelligence could herald the arrival of a “perfect storm” of climate misinformation.

“New generative AI tools make it increasingly easy to produce sophisticated texts, images and videos that are basically indistinguishable from human generated content,” warned the authors. “These technological advances in combination with the amplification properties of digital platforms pose tremendous risks of accelerated automated climate mis- and disinformation.”

Inoculating against deceptive tactics

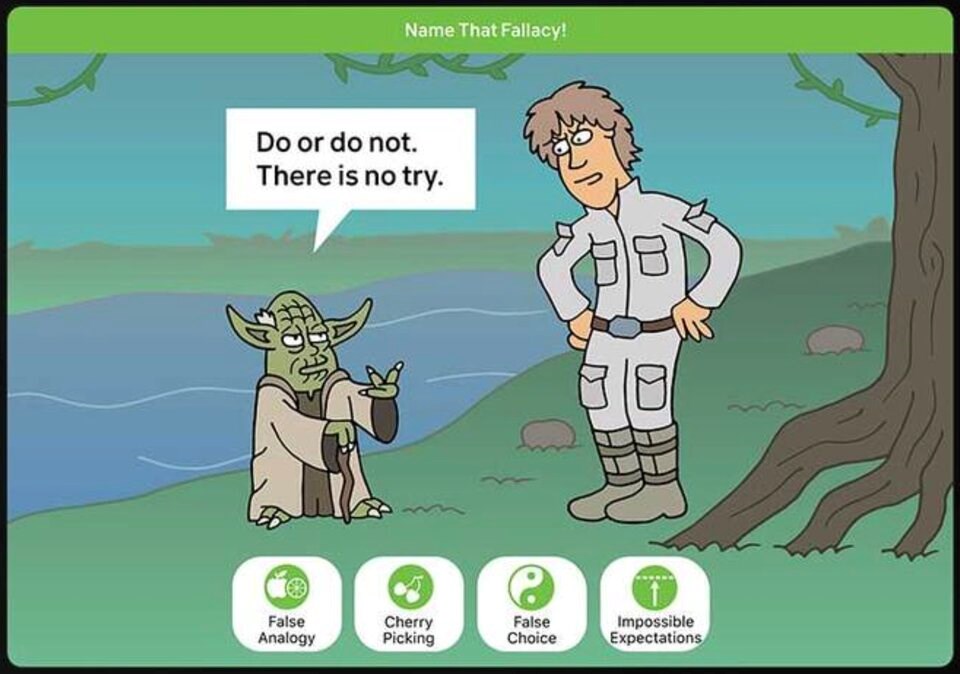

Some have pushed back against the deceptive tactics, using creative tools to engage and inoculate populations against false information. One such tool is the Cranky Uncle game, an interactive app and web interface that trains people to think critically and recognize old rhetorical tools used to deny science and spread false information.

Backed by extensive research, Cranky Uncle attempts puts you in the shoes of a climate denialist, engaging players with humour to recognize arguments that use fake experts, logical fallacies, impossible expectations, cherry picking, and conspiracy theories.

Its creator, Australian research John Cook of Monash University, says the game targets two audiences. The first are those who are the undecided or disengaged from climate change. By providing accurate scientific information, the game inoculates them against future deceitful messaging. The second audience includes people who are alarmed by climate change, but self-censor when talking with others.

“A primary contributing factor to this self-censoring is fear of pushback and being made to look foolish,” Cook and his colleagues wrote in the journal Environmental Education Research in 2021. “For this group, inoculation provides confidence to discuss the climate change issue despite potential dismissive counter-arguments.

“In this situation, inoculation is not about preaching to the choir — rather, it is about teaching the choir to sing.”

The game, which has now been translated into nine languages, has showed enough promise that UNICEF and others have adapted it to fight back against vaccine misinformation.